| And here is another caveat: Some laymen may tend to confuse "motive" and "intent." For example, laymen may think that the suspect's motive (for example, the tobacco sellers' motive) is to make money. Yes, that's indeed so. But that fact is not ALL the truth. That motive is itself what helps confirm the "intent." See Black's Law Dictionary, p 810, which explains as follows:

|

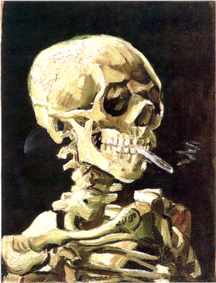

"the unlawful killing of a human being . . . with malice aforethought . . . All murder which shall be perpetrated by means of poison, or by lying in wait, or by any other kind of wilful, deliberate and premeditated killing . . . [is] murder of the first degree." Black's Law Dict, supra, p 1019.Note also the definition of "weapon," "An instrument of offensive or defensive combat, or anything used, or designed to be used, in destroying, defeating or injuring a person."--Black's Law Dict, supra, p 1429. Toxic chemicals, poisons, such as those in Toxic Tobacco Smoke have a long record of being used as weapons.

| The cases of Application of Yamashita, 327 US 1; 66 S Ct 340-379; 90 L Ed 499 (4 Feb 1946), and Application of Honmo, 327 US 759; 66 S Ct 515-517; 90 L Ed 992 (11 Feb 1946), establish that 'negligence' in a government official, in failing to stop third parties from crimes, e.g., from killings, can itself be deemed a crime, in these cases, warranting hanging. (Details at our anti-genocide site and our anti-murder site.)

A simliar culpability concept applies in the private sector, United States v Park, 421 US 658, 672; 95 S Ct 1903; 44 L Ed 2d 489 (1975) (holding private sector official criminally liable for subordinates' acts). When an official refuses to enforce the law, he can be removed from office, Foster v State of Kansas ex rel. Johnston, 112 US 205; 5 S Ct 97; 28 L Ed 696, 697 (10 Nov 1884) (case on removing a prosecutor from office). When a police officer disregards the law blatantly, a criminal conviction can indeed follow, e.g., United States v Luteran, 93 F2d 395 (CA 8, 1937) (conviction of police officer as accessory to crime, due to his not enforcing the law), and in a cigarette case, United States v Sheriff Goins, 593 F2d 88 (CA 8, 1979) (a bribed sheriff case). |

"The defendant was charged with the duty to see to it that . . . life was not endangered; and it is apparent he could have performed that duty . . . " [And] "To constitute murder, there must be means to relieve and wilfulness in withholding relief." Stehr v State, 92 Neb 755; 138 NW 676, 678 (1913) (a case involving a child); Commonwea1th v Hughes, 468 Pa 562, 364 A2d 306 (1976) (a case involving employees, firemen).

18 USC § 1111 - Federal |

MCL § 750.316, MSA § 28.548 - Mich 1st Degree |

MCL § 750.317, MSA § 28.549 - Mich 2nd Degree |

MCL § 750.321, MSA § 28.553 - Mich Manslaughter |

|

|

| "As distinguished from statutory law created by the enactment of legislatures, the common law comprises the body of those principles and rules of action, relating to the government and security [rights] of persons and property, which derive their authority solely from usages and customs of immemorial antiquity, or from the judgments and decrees of the courts recognizing, affirming, and enforcing such usages and customs; and in this sense, particularly the ancient unwritten law of England.

"In general, it is a body of law that develops and derives through judicial decisions, as distinguished from legislative enactments. The 'common law' is all the statutory and case law background of England and the American colonies before the American revolution." People v Rehman, 253 Cal App 2d 119; 61 Cal Rptr 65, 85 [2 Aug 1967]. "It consists of those principles, usage and rules of action applicable to government and security [rights] of persons and property which do not rest for their authority upon any express and positive declaration of the will of the legislature. Bishop v U.S., D C Tex, 334 F Supp 415, 418 [31 May 1971]." Black's Law Dictionary, 6th ed., supra, p 276, and other references, e.g., Martin v Superior Court, 176 Cal 289, 292-293; 168 P 135, 136-137 (11 Oct 1917) and LRA 1918B, 313. See also the book Origins of the Common Law, by Prof. Arthur R. Hogue (Indiana Univ Press, 1966), which cites the deep medieval roots of our legal system. During the early formative period of the common law, between 1154 and 1307, from the reign of Henry II to that of Edward I, common law experienced a spectacular growth as a legal system enforced in the English Royal Courts. In the last chapter, “From Medieval Law to Modern Law," Hogue concludes, “The rule of law, the development of law by means of judicial precedents, the use of the jury to determine the material facts of a case, and the definition of numerous causes of action—these form the principal and valuable legacy of the medieval law to the modern law." |

| Note that one issue in the American Revolution was that colonists complained that they were not being given the benefit of the common law, not given the full rights of Englishmen!

They were familiar with the common law, and with the eminent English writers on the subject, e.g., Lord Chief Justice Edward Coke, Prof. Sir William Blackstone, etc.. American Revolution era people wanted the "common law" here, wanted it so much so as to revolt against Britain for not [according to them] providing it in full. For background on Lord Coke (1551-1633) and 'common law' development, in the face of despotic opposition, see Catherine D. Bowen, "Lord of the Law," 8 Am Heritage (#4) 4-9, 91-95 (May 1957); and The Lion and the Throne (New York: Little, Brown & Co, 1957). For additional references, see, e.g., "When an Act of Parliament [Congress; State] is against common right and reason . . . the common law will control it and adjudge such act to be void."—Dr. Bonham's Case, 4 Coke's Rep, part 8, p 118; 77 Eng Rep 638, 652 (C.P. 1610). And in fact, "Chief Justice Marshall (12 Wheat. 653, 654 [1827)]) lays great stress on the framers of the constitution having been acquainted with the principles of the common law, and acting in reference to them. Most of them were able lawyers; and certainly able lawyers drew up, and revised the instrument. Are we, then, to believe, that if they had any design to take away the common law right, or to authorize congress to take it away or to impair it; they would, knowing the rules of construction cited, and like common law maxims, have used the language they have? There is the strongest reason to believe, from the language, it was adopted for the purpose of preserving it [the right], and to reserve from congress any power over it. This probability arises, almost irresistibly, from the language used; and under the circumstances that it was used. . . . This case, and all the law on this subject, discussed and decided by it, must have been known to the lawyers of the [constitutional] convention." Wheaton v Peters, 33 US 591, 602; 8 Peters, 8 L Ed 1055, 1059 (1834). |

|

'"The very plot is an act in itself.' Mulcahy v Queen, L R 3 HL 306, 317. But an act which, in itself, is merely a voluntary muscular contraction, derives all its character from the consequences which will follow it under the circumstances in which it was done.

"When the acts consist of making a combination calculated to cause temporal damage, the power to punish such acts, when done maliciously, cannot be denied because they are to be followed and worked out by conduct which might have been lawful if not preceded by the acts. "No conduct has such an absolute privilege as to justify all possible schemes of which it may be a part. "The most innocent and constitutionally protected of acts or omissions may be made a step in a criminal plot, and if it is a step in a plot, neither its innocence nor the Constitution is sufficient to prevent the punishment of the plot by law." Aiken v Wisconsin, 195 US 194, 205-206; 25 S Ct 3, 6; 49 L Ed 154, 159 (1904). |

| Tobacco company intent/action when unrestrained by law is shown by this pre-restraint example of smoking—30% of 6 year old boys; 50% of "boys between 9 and 10"; 88% of boys over 11. Source: Dixon, On Tobacco, 17 Canadian Med Ass'n J 1531 (Dec 1927). And see "Sex, Lies & Cigarettes': Vanguard Sneak Peek" (2010) (on modern pusher targeting of children).

"If you are really and truly not going to sell to children, you are going to be out of business in 30 years."--Bennett LeBow, Tobacco CEO, quoted by Georgina Lovell, You Are the Target: Big Tobacco: Lies, Scams—Now the Truth (Vancouver, B.C: Chryan Communications, 2002). Here's an example, see K.B. Lall, F.S.K. Barar, and S.K. Pande, "Probable Tobacco Addiction in a Three-Year-Old Child," 19 (#1) Clinical Pediatrics, pp 56 - 58 (1 January 1980). For a 2004 example of targeting youth, see "Smoking 'em out," by Charles Duhigg, Los Angeles Times (23 Nov 2004) (and using Utah's public land to promote cigarette selling to youths). See also the Movies, Smoking and Teens article in the December 2005 issue of Pediatrics, "The first complete review of research on the link between teenagers viewing on-screen smoking and then taking up smoking themselves finds that one leads to the other. The review concludes that eliminating scenes of smoking in new youth-rated films should substantially reduce smoking initiation in the adolescent years, when the vast majority of smokers start. “'The weight of dozens of studies, after controlling for all other known influences, shows the more smoking kids see on screen, the more likely they are to smoke,'” said lead author Annemarie Charlesworth, a research specialist at the University of California, San Francisco Institute for Health Policy Studies. “This strong empirical evidence affects hundreds of thousands of families.” "A demographic study found that purchases by young smokers are behind the success of certain cigarette brands, the Wall Street Journal reported Oct. 3," says the article "Young Smokers Critical to Brand Success" (4 October 2000). ". . . the clearest statement he heard from RJR headquarters executives came in a question and answer period at a regional sales meeting. Someone asked exactly who the young people were that were being targeted, junior high-school kids, or even younger? The reply came back, 'They got lips? We want 'em,'" says Philip J. Hilts, Smoke Screen: The Truth Behind The Tobacco Industry Cover-Up (NY: Addison-Wesley Pub Co, 1996), on the book jacket. For background on the Hilts book, see Ken Gewertz, "Smoke Screen: Philip Hilts reveals abuses by tobacco companies," in Harvard University Gazette (3 Oct 1996). "Tobacco companies invite young opinion leaders to special events at nightclubs and use direct mail to market to smokers in a low-profile but effective strategy to recruit 18- to 25-year-old smokers," says the article "Tobacco Cos. Recruit Young Leaders to Sell Cigarettes" (23 February 2007). Note that "exposure to smoking in movies predicted risk of becoming an established smoker, an outcome linked with adult dependent smoking and its associated morbidity and mortality," says James D. Sargent, MD, et al., "Exposure to Smoking Depictions in Movies: Its Association With Established Adolescent Smoking," in Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med., Vol 161 (#9) pp 849-856 (September 2007). "The likelihood that an adolescent will become addicted to cigarettes increases with every smoking scene he or she sees in movies, new research indicates," says "Smoking in Films Linked to Adolescents' Habits" (The Washington Post, Science Notebook, Monday, 24 September 2007). See also Joseph Queenan, "Hollywood Stogies," Wall Street Journal, p A9 (21 June 2008). Chyke Doubeni, M.D., M.P.H., George Reed, PhD, and Joseph R. DiFranza, MD, of the University of Massachusetts, "Kids Don't Recognize Signs of Nicotine Addiction" (6 May 2010), citing Pediatrics (doi:10.1542/peds.2009-0238, 3 May 2010): "Young, non-daily smokers experience symptoms of nicotine addiction but often fail to make the connection between cigarettes and the signs of growing dependence." Pushers count on this youthful ignorance, to enable them (pushers) to kill said youths. See the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) rule entitled "Regulations Restricting the Sale and Distribution of Cigarettes and Smokeless Tobacco to Protect Children and Adolescents." 61 Fed Reg 44,396 (28 Aug 1996) (resulting rule codified at 21 CFR § 801, et al.). The FDA found that "cigarette and smokeless tobacco use begins almost exclusively in childhood and adolescence." 61 Fed Reg 45239. Minors are particularly vulnerable to Madison Avenue's exhortations, plastered on racing cars and outfield fences, to be cool and smoke, be manly and chew, and the FDA found "compelling evidence that promotional campaigns can be extremely effective in attracting young people to tobacco products." Id. at 45247. The pushers engage in fraud, even denying that nicotine is addictive! See examples of tobacco effects on children, "Environmental Tobacco Smoke," by Jonathan M. Samet and Sophia S. Wang, in Environmental Toxicants, 2d ed (John Wiley & Sons, Inc, 1999). Nazis were prosecuted for "corrupting young minds" pursuant to the holocaust they caused. Contrast the substantially higher tobacco death rate. For background on Toxic Tobacco Smoke (TTS), click here. |

'once you began the illegal process, enslaving children, selling to children, you can't reap the fruit of your lawbreaking. Otherwise you will continue enslaving/selling to children, as your lawbreaking pays off once they become 18.'Enforcement of the law banning this result would, as some allege, perhaps have the effect that cigarettes would go underground. But enforcement would get cigarettes out of legitimate stores, malls, grocery stores, convenience stores, etc.

| Abortion | AIDS | Alcoholism | Alzheiemr's | Birth Defects |

| Coumarin | Crime | | Drugs

| Heart Disease

| |

| Lung Cancer | Mental Disorder | Seat Belts | SIDS | Suicide |

| "The proof of the pattern or practice [of willingness to commit acts such as the above] supports an inference that any particular decision, during the period in which the policy was in force, was made in pursuit of that policy." Teamsters v U.S., 431 US 324, 362; 97 S Ct 1843, 1868; 52 L Ed 2d 396, 431 (1977).

Violations of criminal law can indeed result in damage to private citizens. Ware-Kramer Tobacco Co v American Tobacco Co, 180 F 160 (ED NC, 1910). Litigants can show as part of the evidence in his/her own case, the guilt of others linked to the current defendant, in showing a pattern. Locker v American Tobacco Co, 194 F 232 (1912). |

| Crime Prevention | Extraditing Pushers | Genocide |

| Government Crime | Medical Statistics | Michigan Law |

| Prosecuting Non-Enforcers | Tobacco Murder | Toxic Chemicals |

| For your own legal research, a useful resource for dealing with the many abbreviations you'll meet, is Mary Miles Prince, Bieber's Dictionary of Legal Abbreviations, 4th ed (New York: William S. Hein & Co, 1993) (often available in the library's reference section). |

|

"Partem aliquam recte intelligere nemo potest, antequam totum, iterum atque iterum, periegerit." "No one can rightly understand any part until he has read the whole again and again."—Black's Law Dict., 5th ed, p 1007 (1979). Meaning: study! |

Michigan Gov. Engler's Support

Exec Order 1992-3 | Law Support Letter # 1 | Anti-Cigarette Smuggling Finding | Law Support Letter # 2 | Governor's Overview |

To Top of This PageTo TCPG Homepage |

The Crime Prevention Group

Email@TCPG